Policy Blog

A primary focus of CCUIH is to advocate for policies that improve the health of American Indian and Alaska Natives. In posting these policy blogs, we aim to bring you current policy priorities and advocacy.

June Updates

Hello everyone! We’ve had a busy year with significant developments at both the federal and state levels. While there has yet to be movement on our key supported federal bills, we’re keeping a close watch and will share updates as they happen. Governor Newsom and Legislators are finalizing California’s budget to address a $56 billion deficit, which could impact UIO funding for essential services. The DHCS webinar on June 24th will discuss authorizing traditional healer services under Medi-Cal, enhancing UIO healthcare offerings. A Supreme Court ruling now requires IHS to cover contract support costs for tribal health programs funded by third-party revenue, potentially increasing UIO funding. We also advocate for an inclusive interpretation of the SSA’s IHS definition. IHS seeks input on funding methodologies for behavioral health initiatives to make funds more accessible and equitable for UIOs. Thank you for your continued support and dedication to our communities. Let’s keep pushing forward together!

STATE UPDATES

- CALIFORNIA BUDGET PENDING FINALIZATION Governor Gavin Newsom and top Democrats are negotiating California’s state budget behind closed doors following the Legislature’s passage of a placeholder budget to meet a mandatory deadline. Key issues include addressing a projected $56 billion deficit over the next two years, with proposals involving dipping into reserves, deferring school funding, and cutting government jobs. The Legislature’s counterproposal seeks deeper cuts to prison funding to protect other programs. Ongoing negotiations must finalize the budget by July 1, 2024.

- Potential Impact to UIOs: UIOs could face funding reductions for critical health and social services they provide to their populations. Potential cuts to public health programs, subsidized childcare slots, and housing development could disproportionately affect these communities, which rely heavily on such support. Additionally, changes in funding allocation and prioritization may limit the capacity of UIOs to deliver essential services, thereby exacerbating existing health disparities and challenges faced by urban Indian populations. We all must remain engaged in advocating for the preservation of funds and programs vital to their communities’ well-being.

- Note: A special CCUIH Impact Report on the New Budget will be sent out the first week of July!

- Contact your legislators

- Write letters: Contact us for Templates to the Governor

- Use Social Media: See our Press Release here

- Share with your Patients for more involvement

- Tribes and Designees of Indian Health Programs Meeting on Traditional Healers and Natural Helpers Webinar 6/24/2024 The Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) is hosting a Medi-Cal Tribal and Designee Webinar to discuss California’s Section 1115 demonstration request, which aims to authorize traditional healer and natural helper services. California submitted this request to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in June 2021, and CMS is now considering the proposal. The webinar will provide information about the proposed approach and seek feedback from participants, with time allotted at the end for questions and comments.

- Potential Impact to UIOs: Enhancing healthcare’s cultural relevance and effectiveness for urban Indian populations. This initiative would allow UIOs to offer a broader range of holistic services, integrating traditional practices with conventional medical care, thus improving health outcomes. Additionally, including these services under Medi-Cal could provide UIOs with increased funding opportunities, supporting the sustainability and expansion of their programs. The proposal could foster greater community trust and engagement by officially recognizing and supporting culturally familiar practices.

FEDERAL UPDATES

- Request for Inclusive Interpretation of Indian Health Service Definition A formal letter was sent to Dr. Reynosa, Director of HHS Region 9, requesting assistance in advocating for an inclusive interpretation of the Social Security Act’s (SSAs) definition of the Indian Health Service (IHS) to encompass UIOs as defined in Title V of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act (IHCIA).

- Response: Dr. Reynosa responded that HHS will work internally with colleagues on this issue and get back to CCUIH.

- FY 2025 Appropriations Update Watch

- The appropriations process for FY 2025, initiated in both the House and Senate, follows the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which caps base discretionary spending at $1.606 trillion, including $895 billion for defense and $711 billion for nondefense. The House has advanced various appropriations bills, with notable progress on defense and other key areas, setting interim 302(b) allocations for subcommittees. This process is crucial for UIOs and health funding, as it will determine the allocation of federal resources impacting health programs and services. Lawmakers are urged to avoid budget gimmicks and consider the long-term trajectory of discretionary spending to ensure sustained support for essential health services.

- Note: At the Senate Interior Appropriations Committee, Sen. Van Hollen asked NCUIH what can be done to address underfunding of UIOs. NCUIH drafted a letter and also provided testimony. More here.

- The appropriations process for FY 2025, initiated in both the House and Senate, follows the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which caps base discretionary spending at $1.606 trillion, including $895 billion for defense and $711 billion for nondefense. The House has advanced various appropriations bills, with notable progress on defense and other key areas, setting interim 302(b) allocations for subcommittees. This process is crucial for UIOs and health funding, as it will determine the allocation of federal resources impacting health programs and services. Lawmakers are urged to avoid budget gimmicks and consider the long-term trajectory of discretionary spending to ensure sustained support for essential health services.

IHS UPDATES

- Supreme Court Ruling on Contract Support Costs On June 7, 2024, Indian Health Service (IHS) Director Roselyn Tso stated the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision requiring IHS to pay contract support costs on portions of tribal health programs funded by third-party revenue like Medicare and Medicaid. IHS has been preparing for this transition to minimize service disruption and urges Congress to shift the IHS budget from discretionary to mandatory funding to ensure stable future funding. The IHS remains committed to supporting tribal self-determination and looks forward to continued partnership with tribal nations. For more information, visit the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website.

- Potential Impact on UIOs: This decision could significantly benefit UIOs by providing increased funding for administrative and operational costs, improving service quality, and enhancing financial stability. If Congress shifts IHS funding from discretionary to mandatory, UIOs will gain more predictable funding, aiding in long-term planning and sustainability. However, UIOs may need to adapt to new administrative systems. This decision emphasizes the importance of continued advocacy and collaboration between UIOs, tribal organizations, and federal agencies.

- IHS Behavioral Health Initiative Funding The Indian Health Service (IHS) is seeking guidance from Tribal and Urban Indian Organization Leaders on funding methodologies for seven behavioral health initiatives, currently distributed through grants, in line with President Biden’s Executive Order 14112. This order aims to reform federal funding to be more accessible and equitable. In fiscal year 2024, IHS administers over $59 million for programs including Substance Abuse and Suicide Prevention, Domestic Violence Prevention, Behavioral Health Integration, Zero Suicide Initiative, and Youth Regional Treatment Centers Aftercar.

- Virtual consultation sessions are scheduled for June 18 and June 20, 2024, with a comment submission deadline of July 22, 2024. For questions, contact Dr. Glorinda Segay at glorinda.segay@ihs.gov.

- Potential Impact on UIOs: The proposed changes to the funding methodologies for behavioral health initiatives could positively impact UIOs by increasing flexibility and accessibility of funds, making the allocation more equitable, and enhancing program support. These reforms aim to reduce administrative burdens, streamline application processes, and ensure UIOs receive adequate funding proportional to their needs.

- Alzheimer’s Grant Program to Address Dementia in Tribal and Urban Indian Communities for fiscal years 2024 and 2025 DUIOLL

- IHS has announced funding decisions for the Alzheimer’s Grant Program toAddress Dementia in Tribal and Urban Indian Communities for FY 2024 and 2025. This aligns with President Biden’s Executive Order 14112, promoting Tribal Self-Determination in healthcare. Following consultations with Tribal and Urban Indian Organization leaders, IHS has allocated over 50% of the program’s budget to grants, small program awards, and pilot development. A new three-year funding opportunity will support up to six new Alzheimer’s program awards, focusing on expansion and sustainability, with a total of $1.2 million annually. Additionally, IHS will continue funding eight existing awardees and has enhanced technical assistance to improve collaboration and best practices among programs.

- Potential Impact to UIOs: This funding has the potential to provide essential financial support for addressing dementia. The allocation includes over 50% of the program’s budget for grants, small program awards, and pilot development, focusing on sustainability and expansion planning. This funding will enable UIOs to develop and refine culturally informed care models, improve collaboration with other IHS, Tribal, and Urban Indian programs, and explore new billing opportunities through CMS. These measures may enhance UIOs’ capacity to deliver effective dementia care and support long-term program viability.

POLICY ENGAGEMENTS IN JUNE:

- CalWellness

- CPG

- CDSS Tribal Advisory Committee

- CDPH Tribal Data Workgroup

- CPEHN Board Meeting

- Testify on SB 1065. Healing Arts Expedited Licensing

- CPCA Biweekly Member

- RAC Monthly Directors

- Pathway to Healing – The California Endowment

- Native Health Data UCSF

- CPCA CEO Peer Network

- NCUIH Policy Workgroup

- UIO Site Visit NAIC

- IHS Urban Confer Behavioral Health

- OUIHP Urban Programs

- CDPH Tribal Advisory

- Health Career Connect Regional Health

- CPCA Legislative and Regulatory

- IHS, NCUIH, CCUIH All Inclusive Rate

- DHCS Traditional Healers and Helpers

- Training MCO Ballot Initiative

- Dental Therapy Allies

- California Racial Equity Coalition: Department and Agency Accountability

Legislative Report prepared by CCUIH Director of Policy & Planning Nanette Star nanette@ccuih.org and CCUIH Executive Director Virginia Hedrick virginia@ccuih.org

Unlocking Healthcare: The Journey for American Indians and Alaska Natives

Welcome back, readers! Let’s dive into the intricate world of healthcare access for American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN). Join us as we unravel the layers of services available, and the promises made to these communities.

Part 1: Navigating the Healthcare Maze

Imagine a world where access to healthcare isn’t just a matter of picking up the phone and booking an appointment. For AI/AN communities, it’s a journey through a maze of options, each with its own twists and turns.

First up, we have the Indian Health Service (IHS). Picture this: a federal agency dedicated to providing healthcare services to AI/AN folks, with facilities dotted across reservations and tribal lands. Sounds great, right? Well, here’s the kicker – IHS steps in only when all other payment avenues have hit a dead end. It’s the safety net, the payer of last resort, ensuring that healthcare isn’t just a privilege for those with deep pockets.

But wait, there’s more! Many tribes run theirown healthcare programs, tailored to fit the unique needs of their communities. These programs, often in partnership with IHS, bring healthcare closer to home, quite literally. And let’s not forget our urban AI/AN community– Urban Indian Health Programs swoop in to fill the gap, offering everything from primary care to behavioral health services.

Now, you might be pondering the realm of insurance coverage. Certainly, navigating through the intricate systems of Medicaid, Medicare, and private health insurance can be perplexing. While AI/AN individuals hold eligibility for these programs, the situation is nuanced. Despite potential supplementary benefits and services geared towards AI/AN communities, substantial gaps persist in obtaining vital care. It’s crucial to acknowledge these discrepancies rather than assuming they receive inherently superior healthcare options.

Part 2: Promises and Legal Obligations

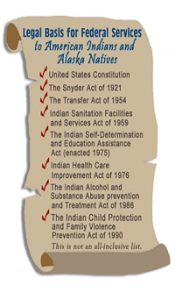

Let’s rewind a bit and talk about promises. Did you know that the U.S. government is legally bound to provide healthcare to AI/AN communities? It’s not just a handshake deal; it’s written in treaties, statutes, and court decisions.

Enter the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA). This game-changer allows tribes to take the reins, managing their own healthcare programs and calling the shots. It’s about time tribes had a say in their own well-being, don’t you think?

Ever wondered about the unsung heroes behind the scenes of healthcare access for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities? Enter the Indian Health Care Improvement Act (IHCIA), the superhero of legislation promising better days ahead. But here’s the twist: it’s not just about tribal lands. Urban Indian organizations are the dynamic sidekicks making waves within the IHCIA narrative. They’re the bridge connecting AI/AN populations in urban areas to essential healthcare services. Picture this: bustling city streets where cultures collide, yet healthcare remains a priority. Urban Indian organizations step up, ensuring that the IHCIA’s reach extends far beyond reservation borders. In this tale of healthcare equity, these organizations emerge as indispensable allies, championing inclusivity and effectiveness in healthcare delivery for AI/AN individuals nationwide. So, next time you think about healthcare heroes, remember the urban warriors working tirelessly behind the scenes to make a difference in AI/AN communities everywhere.

within the IHCIA narrative. They’re the bridge connecting AI/AN populations in urban areas to essential healthcare services. Picture this: bustling city streets where cultures collide, yet healthcare remains a priority. Urban Indian organizations step up, ensuring that the IHCIA’s reach extends far beyond reservation borders. In this tale of healthcare equity, these organizations emerge as indispensable allies, championing inclusivity and effectiveness in healthcare delivery for AI/AN individuals nationwide. So, next time you think about healthcare heroes, remember the urban warriors working tirelessly behind the scenes to make a difference in AI/AN communities everywhere.

Now, let’s address the elephant in the room – the challenges. Underfunding, geographic barriers, legal complexities – you name it, AI/AN communities and urban Indian populations have faced it. But here’s the thing – challenges are just opportunities in disguise.

Imagine living in a remote village or in the heart of a bustling city’s concrete jungle, miles away from the nearest healthcare facility. That’s the reality for many AI/AN folks, whether residing on reservations or in urban areas. And let’s not forget the red tape – navigating the legal and administrative maze can feel like a Herculean task for both tribal and urban Indian health organizations.

But amidst the chaos, there’s hope. Cultural competency, language support, and a sprinkle of historical healing practices – these are the building blocks of a healthcare system that truly serves AI/AN communities, wherever they may be found.

The Ugly Truth: Government Hurdles and Broken Promises

However, let’s not sugarcoat it – the journey to accessible healthcare is far from easy. The federal government doesn’t always make it simple, and promises aren’t always followed through.

Despite legal obligations and treaties, AI/AN communities still find themselves grappling with underfunded programs, bureaucratic hurdles, and unfulfilled promises. It’s a harsh reality that underscores the ongoing struggle for equitable healthcare access.

Conclusion: A Call to Action

As we wrap up our journey through the world of AI/AN healthcare, one thing becomes clear – access to healthcare isn’t just about doctor’s appointments and prescriptions. It’s about empowerment, self-determination, and honoring the promises made to Native communities. So, here’s to unlocking healthcare for all – one step, one promise, and one community at a time. Because when it comes to health, everyone deserves a seat at the table. Let’s make it happen, together.

9 Key Policies for AI/AN Health Care Improvements

1. Increased Funding for Indian Health Service (IHS) and Tribal and Urban Health Programs: Advocate for increased federal funding for the IHS and tribal and urban health programs to ensure sufficient resources for healthcare services, facilities, and staffing in AI/AN communities.

2. Strengthening the Indian Health Care Improvement Act (IHCIA): Advocate for strengthening and reauthorization of the IHCIA to enhance healthcare access, quality, and tribal self-governance, while also addressing gaps in services and improving coordination with other healthcare systems.

3. Expansion of Medicaid and Other Health Insurance Programs: Advocate for expanding Medicaid eligibility and improving access to health insurance coverage for AI/AN individuals, including through Medicaid expansion in all states and ensuring culturally competent enrollment assistance.

4. Investment in Telehealth and Telemedicine Services: Advocate for increased investment in telehealth and telemedicine infrastructure to expand access to healthcare services, particularly in rural and remote AI/AN communities where access to care is limited.

5. Support for Urban Indian Health Programs: Advocate for continued support and funding for Urban Indian Health Programs to ensure access to culturally competent healthcare services for AI/AN individuals living in urban areas.

6. Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Advocate for policies that address social

determinants of health, such as housing, education, and economic opportunities, which disproportionately impact AI/AN communities and contribute to health disparities.

7. Improving Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services: Advocate for increased resources

and funding for mental health and substance abuse prevention, treatment, and recovery programs tailored to the unique needs of AI/AN communities.

8. Enhancing Healthcare Workforce Diversity and Cultural Humility: Advocate for policies to increase the diversity of the healthcare workforce and promote cultural humility training, going beyond competency, for healthcare providers to improve the quality of care for AI/AN patients.

9. Protecting and Expanding Tribal Sovereignty: Advocate for policies that uphold and strengthen tribal sovereignty, including the ability of tribes to govern their own healthcare systems and determine their healthcare priorities.

By advocating for these policies, individuals and organizations from all backgrounds can contribute to achieving greater equity, access, and quality in healthcare for American Indian and Alaska Native communities. This collective effort will ultimately lead to improved health outcomes and well-being for Native peoples across the United States, fostering a more inclusive and equitable healthcare system for all.

Unveiling the Epidemic: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP)

In recent years, the issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP) has garnered increasing attention, shedding light on a deeply entrenched crisis affecting Indigenous communities across the globe. Beyond being a mere statistic, MMIP represents a profound human tragedy, exposing systemic failures in societal structures and law enforcement agencies. As we delve into this pressing matter, it’s crucial to explore not only the social and cultural implications but also the health policy dimensions that intersect with this multifaceted issue.

Understanding the Crisis

The MMIP crisis encompasses a spectrum of tragedies, including cases of Indigenous individuals disappearing under mysterious circumstances, often with little to no investigation or media coverage. Alarmingly, Indigenous women, girls, and Two-Spirit individuals are disproportionately affected by this crisis, facing heightened risks of violence, exploitation, and disappearance. Rooted in historical trauma, colonization, and systemic racism, the MMIP epidemic reflects broader patterns of marginalization and injustice faced by Indigenous peoples worldwide. MMIP started as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and was first established as a movement in Canada where the grassroots efforts to raise awareness found footing around 2015.

Health Policy and MMIP

The MMMIP crisis is a deeply entrenched issue that transcends mere criminal justice and human rights concerns. Its impact reaches far into healthcare systems, exacerbating existing health disparities within Indigenous communities. To address this multifaceted challenge effectively, here are some key health policy considerations within the MMIP discourse:

Crisis Response and Mental Health Support: Health policies must prioritize culturally sensitive crisis response mechanisms and mental health services tailored to the needs of MMIP families and communities. This includes trauma-informed care, grief counseling, and support services for those affected by the loss of a loved one.

Preventive Health Measures: Addressing the underlying factors contributing to the vulnerability of Indigenous populations is paramount. Health policies should focus on preventive measures, such as community-based programs targeting substance abuse, domestic violence, and socioeconomic determinants of health.

Data Collection and Surveillance: Improved data collection and surveillance systems are essential for accurately capturing the scope and scale of the MMIP crisis. Health policies should mandate the collection of disaggregated data on Indigenous health outcomes, including rates of violence, trauma, and mental health disorders.

Cultural Competency and Indigenous Healing Practices: Health practitioners and policymakers must prioritize cultural competency training and incorporate Indigenous healing practices into mainstream healthcare systems. This includes recognizing the role of traditional healers, elders, and community leaders in promoting holistic wellness and healing.

Collaborative Approaches and Partnerships: Effective responses to the MMIP crisis require collaboration across multiple sectors, including healthcare, law enforcement, tribal governments, and advocacy organizations. Health policies should facilitate interagency coordination and establish formalized partnerships to address the complex needs of affected communities.

Moving Forward: Advocacy and Action As advocates and policymakers continue to amplify the voices of MMIP families and demand justice for those lost, the integration of health policy perspectives becomes increasingly critical. By recognizing the interconnectedness of health, justice, and Indigenous rights, we can work towards holistic solutions that address the root causes of the MMIP crisis and uphold the dignity and well-being of Indigenous peoples everywhere.

5 Ways to Engage in Health Policy on MMIP

- Advocate for Legislation: Support or advocate for legislation at local, state, or federal levels that addresses the MMIP crisis. This may include advocating for increased funding for law enforcement efforts, victim services, or prevention programs. (See Resources below for California Assembly Bills)

Contact your representatives:

Find your CA State Senate & Assembly members: https://findyourrep.legislature.ca.gov/

Find you members of Congress: https://www.congress.gov/members/find-your-member

- Raise Awareness: Organize or participate in events to raise awareness about MMIP within communities, educational institutions, or healthcare settings. This can include hosting panels, workshops, or distributing educational materials.

- Community Partnerships: Collaborate with tribal governments, law enforcement agencies, non-profit organizations, and healthcare providers to develop comprehensive strategies for addressing MMIP. This could involve forming task forces, advisory boards, or community-led initiatives. Click here to find MMIP State Resources.

- Data Collection and Research: Support efforts to improve data collection and research on MMIP by advocating for the development of standardized protocols for reporting and investigating cases. Encourage funding for research studies to better understand the root causes and systemic factors contributing to MMIP.

- Policy Recommendations: Develop and promote policy recommendations aimed at addressing systemic issues contributing to MMIP, such as jurisdictional complexities, lack of resources for victim services, and cultural competency training for law enforcement and healthcare providers. These recommendations can be presented to policymakers, government agencies, and advocacy groups to inform policy development and legislative action.

Additionally, individuals can engage by contacting representatives, staying informed about policies, connecting with loved ones, and sharing stories of MMIP, resilience, and healing. Together, we can make a difference in addressing the MMIP crisis and creating a future where every Indigenous person is valued, protected, and able to thrive in safety and dignity.

California Policies to Follow

Assembly Bills:

44 California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System: tribal police.

81 Indian children: child custody proceedings.

85 Social determinants of health: screening and outreach.

373 Intersession programs: foster children and homeless youth: priority access.

630 Department of Transportation: contracts: tribes.

912 Strategic Anti-Violence Funding Efforts Act.

1574 Murdered or missing indigenous persons.

Feather Alert System: A Feather Alert is a resource available to law enforcement agencies investigating the suspicious or unexplainable disappearance of an indigenous woman or indigenous person. The Feather Alert will provide immediate information to the public to aid in the swift recovery of missing indigenous persons. https://a45.asmdc.org/press-releases/20231207-ramos-commends-la-city-council-helping-implement-feather-alert-system

Learn More

Policy Recommendations:

A Policy Story in 6 Steps

A primary focus of CCUIH is to advocate for policies that improve the health of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Through our blog, we will bring you current policy priorities and advocacy. This year’s first blog will explore the six primary policy elements.

Policy tells a story; like all stories, there is a problem to solve or overcome and a solution. To better understand the 6 primary policy elements, I will take you through a story that has impacted my life and maybe yours. At the age of 3, my mother contracted wild polio. At this time, in the 1950s, polio paralyzed more than an estimated 15,000 people each year, and at its peak in 1952, the U.S. reported 57,628 cases, 3,145 deaths, and 21,269 people struggling with mild and disabling paralysis.

In 1952, right before polio’s peak, my mother spent three months in the hospital, strapped to a board and isolated. Once she returned home, she required physical therapy three times a day. She graduated from casts to braces to walking unassisted but with a limp and permanent paralysis diagonally across her body. Her story didn’t end there. We have learned that this disease returns. She now has post-polio syndrome and is back to braces and a walker for mobility, as well as requiring constant care.

Fortunately, years later, widespread vaccination campaigns have helped to eliminate many debilitating diseases, including polio, all facilitated through the policy process. Let’s dig deeper into the policy elements that helped eradicate wild polio.

Policies are not necessarily laws but can take the form of laws, regulations, and bills. I like to think of policy as the how-to to get where we want to go, like a road map to address an issue. And, like any roadmap, there are different turns we can take along the way to get to the same destination, and sometimes these are shortcuts and other times detours. Below, under each policy element, will be an example that led to polio eradication in the United States.

Six Policy Elements

1. Define the Problem

In this first step, we must define the problem. Perhaps a situation has emerged suddenly, or a problem has grown, so it must be addressed. Sometimes, an issue has been present for decades, and then a group or individual brings the problem to the forefront. A problem may be a foreshadowing so that the definition could be built on the expectation of a future crisis and the policy is preventative. Regardless of how the problem emerges, we must define the issue to start working toward a solution.

Example: Cases of polio continued to rise, becoming a public health issue with several epidemics occurring between 1948 and 1955.

2. Set the Agenda.

In this second step, we can assemble evidence and put the problem on a policy agenda to get decision-makers’ attention. Setting the agenda is essential to ensure the problem will be examined and, hopefully, a solution will be proposed and implemented. This step is also where we assemble evidence for the issue to highlight its importance and impact.

In this step, I ask myself the 5 Whys to understand the situation’s root and ensure I ask the right question to solve the problem.

Example: Before a vaccine was readily available, and with case counts so high that included death and mild to severe paralysis, parents were fearful of letting their children out of the house and even playing with others. Children stopped going to school, and communities were distraught. Case counts continued to rise, and it was clear a polio vaccine needed to be a priority to protect the country’s health, economics, and social structures. This priority agenda-setting quickly led to the first polio vaccine being licensed and ready for distribution in 1955.

Furthermore, when we ask ourselves the Whys regarding high cases of polio, this is what we find:

Why are polio rates so high?

Increased cases are because polio spreads very quickly and easily through person-to-person transmission.

Why is polio spreading so quickly?

Children have the highest case rate due to their lack of sanitation and proximity to one another, increasing transmission.

Why is lack of sanitation and proximity more likely with children?

Children are more likely to put items in their mouths, including their fingers, after touching random surfaces. Also, children congregate together in schools, pools, and daycare centers.

Why do children congregate?

We need children to be socialized and learn in a group setting as part of their healthy development.

Why do we need children to be part of a group and societal system?

Children grow up to be adults.

We do not always need to ask additional Why questions if a root appears in any previous questions. I often ask one more why, in case there are multiple roots. The final root is evident in this case, and the pertinent details are in the prior Why responses.

3. Consider Options

At this point, the policy agenda is set to include an identified problem. Now, we get to continue to use the roots we identified in the 5 Whys statement to develop considerations. In this step, decision-makers should consider the options when determining a solution. Consider including the potential opposing arguments to each proposed solution.

Example: In this case, the vaccine was now available. However, the problem remained: how to prevent children from contracting polio and decrease the disease’s overall prevalence for years to come. Like many roadmaps, sometimes you may have a destination in mind. In this case, the destination or goal was to create high immunity (protection) within populations to slowly lead to eradicating the disease. We know that special consideration should include children and their socialization needs.

Potential Options:

A. Keep children home until cases decrease

B. Ensure all children are vaccinated

C .Provide vaccination guidance

D. Close all communal child gathering areas such as pools and daycares

E. Vaccinate annually

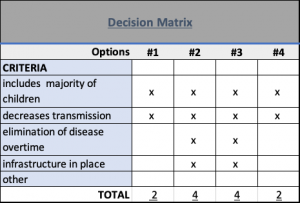

4. Selecting Criteria

When we make decisions, we do this based on criteria. In policy, we typically collaborate with others, and it is more effective when groups, stakeholders, and decision-makers agree on the criteria. Sometimes, these are all the same people or groups, and sometimes they differ. A shared criterion acts as an agreement on how considerations are weighed to arrive at a decision. To help guide these conversations, I use a Decision Matrix to find common ground. Think of this as how you decide where on your roadmap you want to take a turn or if you will include a detour or a shortcut. What will you gain, and what may you lose? What are the most important factors when deciding, such as time, money, number of people impacted, etc.?

Example: In this example, the decision-making group selected the criteria to include children, decrease transmission, eliminate the disease, and have infrastructure already in place. The total scores clearly show that multiple options fit the requirements listed. Sometimes, the best solution may be the result of combining various options.

5. Implementation

This fifth step is where programs are created or modified, or some action step occurs to implement the proposed solution. Picture the scene when the problem has a resolution (s) and what will be required to administer, such as what people or groups may need to be included, who will take ownership in implementation, evaluation, and other strategies.

Example: Childhood immunization was proposed to help eradicate polio in the United States. This solution included guidance recommending that four doses of the polio vaccine be given to children before or by the first day they enter school. Over time, the cases declined sharply to less than 1000 cases in 1962 and remained below 100 cases after that year.

6. Monitoring and Evaluation

This last step is to identify the impact of the policy by asking many questions, such as: Did we solve what we were trying to solve? How many people were reached with this solution? Are there any groups of people that may still be affected by this initial problem (look at the equality and equity of the solution)? Is the problem still prevalent, and how much has it changed? Should anything be added or retracted from the implemented solution to be more equitable? Asking questions allows us to accurately account for the process and see where we may need to go back and make adjustments. Ensure that the evaluation metrics include more than quantitative analysis, such as qualitative information from the impacted community and other culturally applicable measures. A different team or group of leaders may guide the evaluation to ensure the policy implementation has efficacy and remains valid.

Example: Polio has since decreased globally by 99%, with only two countries reporting wild polio cases.. Monitoring and evaluation of polio continue today and include governmental and non-profit organizations often working together. Another part of this story is childhood immunizations, and there continue to be cases of diseases we once thought were eliminated that resurface in communities when children are not vaccinated. Continuous monitoring and evaluation of vaccination guidance is necessary to ensure the effectiveness of these strategies. The evaluation process also helps us uncover lessons learned.

Using the policy process can facilitate many phases of disease eradication. The examples above demonstrate six policy elements that can drive change. This work came too late to change my mother’s life. However, her perseverance and strength through this debilitating disease continue to inspire me to work toward using policy to make positive change, especially regarding health and our American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Remember that these policy elements are not always linear and often need to be repeated to ensure the problem does not reemerge. Specifically, the Monitoring and Evaluation steps for polio eradication continue to keep our communities safe and children healthy and are helping to eradicate polio worldwide.

CCUIH will be releasing a monthly blog throughout 2024. If you have policy topics or questions you’d like to see covered, please contact nanette@ccuih.org.